Nepal: Hiking from near Kathmandu to Everest Base Camp

Nepal: A daily trekking diary

Hiking in the Himalayas for a month while trekking on a trail with a total elevation change of 61,000 feet was a challenge that tested of the skills we’d learned in all our previous travels. The task seemed relatively easy by just looking at a map of our route; approximately 125 miles of ‘teahouse trekking’ – sleeping & eating at lodges established along the trail – could hardly be considered hard core. Yet this journey to Everest Base Camp held special significance for us. It was the culmination of our 14-month trip, our last destination before returning home.

Breathing in the crisp dry air of Kathmandu, Nepal’s 4,000-foot high lively capital city, we relished a lively atmosphere that is completely different from the tropical climates in SE Asia we’d become familiar with during the past six months. Tucked away in the crooked narrow streets in the heart of the bustling tourist center of Thamal – a jumble of cashmere pashmina shops, outdoor gear stores, bakeries, and Tibetan Thangka art galleries – is the historic Katmandu Guest House, our home for our first three nights. It was here, while running errands to prepare for our trek, where we were introduced into Nepalese culture by a handful of local characters.

Our first encounter was with Raaj, owner of Tea World; he welcomed us into his shop for an impromptu tea tasting & kept us there for hours with his charismatic demeanor & contagious laugh. Coincidentally he’s also a trekking guide, who provided us with many handy tips and even his lucky walking stick to assist us on our way. On Halloween we were invited to Raaj’s home where his talented daughter entertained us by singing songs and reciting poetry while we warmed up for a mysterious night on the town. A local rock band – friends of Raaj’s – was scheduled for a special holiday performance & we were invited. Raaj’s beautiful Indian wife and her girlfriends dressed up in evening wear while Dale & I along with two of Raaj’s friends joked about our ‘budget travelers’ costumes. Since Raaj was vague about our destination and casual in both his jeans and demeanor, we were very surprised when our taxi pulled up in front of the five star Hyatt Regency. Luckily it didn’t really matter how we were dressed since the recently opened hotel only had an occupancy rate of 5% and the fancy bar was nearly empty. We all had a memorable night dancing to the classic rock music & enjoyed our private show.

On our second night in Katmandu the owners of the Lotus Gallery invited us to their home for dinner – a special Indian variation of Nepal’s national dish, Dal Baat. Sitting on the floor in their tiny but comfortable apartment eating with our fingers, we considered ourselves lucky to have met such welcoming hosts who allowed us to glimpse a taste of their everyday life. The next day after shopping for Christmas presents and souvenirs, we prepared to leave the comforts of our haven in Kathmandu and set off for our 30-day trek.

Day 1: Jiri

Of the many trekking options in Nepal, we chose to do the ‘expedition route’ – the original passage early expeditions walked to Mt. Everest. Since all since vehicle roads into the mountains end in Jiri (a day’s journey from Katmandu), this trail begins in the foothills of the Himalayas 100 miles away from Everest Base Camp. In these relative lowlands (5,000 feet to 11,000 feet) we discovered it’s still possible to witness the traditional life of subsistence agriculture that has remained virtually unchanged for the past several centuries. Now most trekkers heading to Mt. Everest bypass the lowland region, flying in & out of Lukla (elevation 11,000 feet) to shorten their time on the trail and skip the difficult valley traverses. Additionally most westerners want to avoid a grueling daylong local bus ride from Kathmandu to Jiri, the only transportation option other than hiring an expensive private vehicle & guide.

Inadvertently we chose a non-express local bus, turning the normal 8-10 hour trip into 13 long teeth-clenching hours. Every 15 minutes our bus stopped for some reason: for a smoke break, snacks, the toilet, to pick up more passengers, and for various unknown reasons. We thought the bus was full after two dozen army boys, en-route from the Katmandu to Jiri military base, crammed themselves and their many bags on board. However we were amazed that another 30 or so passengers were able to fit on our retired school bus by sitting on a skinny wooden bench placed in the isle and on a rack fastened to the roof of the bus.

PHOTO: crammed bus (scan)

By the time we reached Jiri at 10 p.m. we didn’t care where we slept – we were just happy to have finally arrived. We ended up staying at one of the last available rooms – for good reason – since all better lodges were already full. All night the cockroaches and mice scurried above our bed; thankfully it was so dark we couldn’t see what other creatures lurked nearby and so tired we didn’t have the energy to fight them off. With this inauspicious beginning we hoped our journey wouldn’t become progressively more difficult. From day one we knew we had started an adventure unlike any we had experienced before.

Day 2: Shivalaya

After sleeping in until 9 a.m. (a rare luxury on the trail) we decided to take it easy for our second day of walking. Since we’ve been backpacking for over a year now some people may assume that it wasn’t difficult for us to carry our own packs vs. hiring a porter to carry everything for us. Although we significantly reduced our normal loads by scrutinizing the necessity of every single item, our packs were still not light (mine was 27 lbs., Dale’s was 38 lbs.). We quickly discovered there’s a big difference between walking with our packs all day on steep trails in high elevation and any backpacking we’d done previously.

Shivalaya, the town where we stopped on our second night, was a vast improvement over Jiri. Several lodges (Nepal’s rustic version of a Bed & Breakfast) were scattered around the center of this small settlement and we were happy to find a nice Nepalese home where we were the only guests. By walking at a slower pace and covering less daily distance than the average trekker we started a trend of staying in towns that weren’t popular overnight stops. Whenever possible we also always chose to stay with a Sherpa family, the ethnic group well known for their mountaineering skills and hospitality. That evening we chatted with the owner about village life and the jackals howling in the distance while his wife cooked up a tasty dinner and their children peered at us curiously.

Day 3: Deorali

On our third day of walking we experienced our first difficult valley traverse. We climbed nearly 3,000 feet in elevation to the 8,875-foot Deorali Pass. Cool clouds were rolling up the valley during our trek so we decided to stop at a hilltop lodge to warm up with some hot milk tea & homemade apple pie. Since the view and food were so good we decided to stay here for the night. Surprisingly this Sherpas house had electricity (many in the lowlands didn’t) and we sat huddled with the family around the wood fired stove in the green tinted glow of their television. A Nepal version of star search was playing; in an intriguing twist the aspiring stars sang traditional Nepal songs.

PHOTOs: Deorali lodge with Dale in window, Andrea with lodge owners

The next morning was crystal clear and at sunrise we saw our first glimpse of high snow covered peaks around the surrounding hills.

Day 4: Kenja

We spent all of today descending the 3,000 feet we had gained yesterday. At first the trail was surprisingly steep, then suddenly it disappeared completely into a dry streambed. We scrambled along rocks hoping we were continuing in the right direction: When the telltale mule dung soon appeared – a common occurrence along the main route – we knew we were on the right track. Luckily this was the sunny, dry season in Nepal; we couldn’t imagine navigating this section of the trail during the monsoons.

Many terraced farms growing rice, fruit, and vegetables filled the next valley. Colorful clumps of cornhusks hung drying from nearly every rooftop, huge red chili peppers spread in baskets to bake in the sun, and women sat along the trail beating wheat stalks by hand. Rice fields were being cultivated by hand or buffalo-powered plows, creating interesting geometric patterns from our vantage point above. The whole family joined in the harvest and even the cows munched and chickens pecked at the rice scraps.

Unfortunately this charming scenery was occasionally marred by disturbing encounters with village children. One girl, about 7 years old, approached us insistently with a phrase we would soon become accustomed to hearing: “Hello, pen?!” She was surprisingly fluent in select English phrases – “Hello, watch?” – “Hello bracelet?” – “Hello, necklace?” – “Hello photo?” – “Hello sweets?” and could recite the alphabet and count to at least 25 (we stopped her there). To the unsuspecting tourist her antics may have been cute and clever: To us they posed a difficult moral dilemma; every phrase asked us to give her some item we carried – jewelry, food, or money. We decided against the easy solution, which would have been to have given into one of her demands. Our reaction may seem cold in light of the incredible poverty of rural Nepal and the relative monetary wealth that western money represents (the annual family per capita income in Nepal is only $200 U.S.). Travelers before us undoubtedly began this “hello, pen?!” trend which taught kids that they were poor because they didn’t have things common in ‘developed’ countries. Well-meaning trekkers provided candy without considering the consequences; without access to dentists, toothbrushes, or toothpaste kids began getting cavities. Most children in these lowland areas didn’t have easy access to schools, know how to write, or even have paper, so we wondered what they would do with a pen if we gave them one. We had a funny picture in our minds of kids visualizing trekkers as walking pen-dispensing machines. Most trekkers travel with a porter carrying their supplies so they would have plenty of space to hold dozens of pens. Perhaps the kids think the primary reason trekkers visit their village is to dispense pens – it’s probably inconceivable to them why anyone walk so many miles to just look at the scenery. In some villages we saw a donation box to help build a school or for the community, which was a much better alternative than encouraging begging for unnecessary items.

That afternoon we reached the bottom of the valley and stopped at a town named Kenja, which is nearly 1,000 feet lower than Jiri. It was warm at this low elevation so we decided to try our first wood-fired ‘hot’ shower. The bathroom was made with a stone floor and walls in a small separate building from the lodge. At first the water trickling from the showerhead was scorching hot, then pleasantly warm for about a minute, after which it rapidly became frigid. Needless to say we learned that ‘hot shower’ is interpreted in many ways and to shower quickly and efficiently.

Day 5: Dagchu

Today was our most strenuous section of hiking so far; we climbed over the 11,581 foot Lamjura Pass, which is 6,201 feet above our starting point in Kenja. In order to break up this long ascent we stopped overnight midway up the pass. I found the steep trail was bearable if I walked at a slow constant pace, but unfortunately it was difficult to maintain this rhythm when mule and porter trains constantly passed us then stopped ahead to rest in the middle of the trail. Contrary to what we were accustomed to, the trail etiquette in Nepal did not encourage politeness. Like a lion that asserts dominance over its home territory, the porters and mules always barged ahead forcing us to step to the side of the narrow trail. Irritated, I longed for the day I would become fit enough to continue on my way uninterrupted. The higher we hiked the more relentless the trail became – never once did its steep grade flatten. After a difficult 5-hour crawl up 4,000 feet we stopped at a small settlement, Dagchu (9,350 feet). Our accommodation choices were limited so we found ourselves stuck at one of the most basic ‘huts’ we’d encountered. The usual cool afternoon fog had traveled up the valley so we huddled inside the kitchen squinting in the dim, smoky light since there was no electricity and few windows. This was the first night we didn’t stay with a Sherpa family, but the young Nepalese couple was friendly and interesting. It was cool at this elevation – I bundled up in my sleeping bag in the kitchen/ dining room to keep warm since their old, small wood stove didn’t produce much heat. We wondered how anyone could see by the dim candlelight to prepare dinner, so we ordered a hearty and simple to prepare dish of Dal Baat without meat.

Near 7 p.m. two Nepalese joined us to warm up with hot milk tea and food. At first we thought they may be Nepal soldiers – they looked like the army boys we met on our bus ride to Jiri. Dale asked to see their guns and was amazed to discover that they were heavy wooden musket-style rifles. Dale asked, “How long does it take to reload?” and he replied, “About 3 minutes”. “Boy, you better be a good shot then”, Dale joked and we all laughed. We began to become curious why they were traveling at night and when we inquired “Where are you headed?’ their answers were evasive. Though reserved they were polite towards us and quite articulate in English for young men (probably about 18-21 years old). We left them in the lodge talking with the owners to turn in early to our room in the lodge next door. Later we realized that they must be Maoists, members of an organization that has been active in Nepal the past decade trying to overthrow corrupt government officials. They are known as ‘Robin Hood’ crusaders – they travel at night through rural areas to bomb police and government buildings in protest and to steal their money to redistribute to the poor. Tourists are strictly off limits to the Maoists since tourism is one of the primary sources of income for villages along the trail. When telling other Nepalese about our encounter, most were amazed that we actually met Maoists and happy that we ran into no trouble.

Day 6 & 7: Junebesi

On our second day of climbing over the difficult Lamjura La Pass we encountered another obstacle– I woke with a queasy stomach so we left without breakfast. We only made it about 45 minutes before I had to rush into the bush along the trail and experienced my first bout with travelers diarrhea. After another few hours of struggling and sudden stops, we finally made it to the top. About this time it began to hail and the trail seemed to traverse along an exposed ridge forever. Hail turned to sleet then a heavy downpour as we descended down the other side of the pass into the next valley. We were quite relieved when we finally reached Junebesi 2,700 feet below. Resolved to take a rest day tomorrow, we searched for a good place to relax and were delighted to find the Apple Orchard Guest House, a beautiful new lodge with a polished wooden interior and a comfy warm lounge room. We thoroughly enjoyed nice hot showers in the insulated bathroom inside the main lodge (a nice change) and the best fresh-baked apple pie we’d tasted so far. This lodge was the first we’d encountered that was busy with other trekkers, but we enjoyed their company.

The next morning we ate a late breakfast outside on a sunny patio that overlooked the apple orchard. After most guests had left for the day we sat chatting with the owner who has traveled to America several times. Dale asked his wife about the fancy fur hats he had seen in photographs and before we knew it she brought down not only their fur hats but also their entire wedding clothes for us to try on! The whole family got a laugh seeing us dressed up in the special ceremonial outfits and we all had fun with the photo shoot.

PHOTO: us with Nepalese in ceremonial outfits

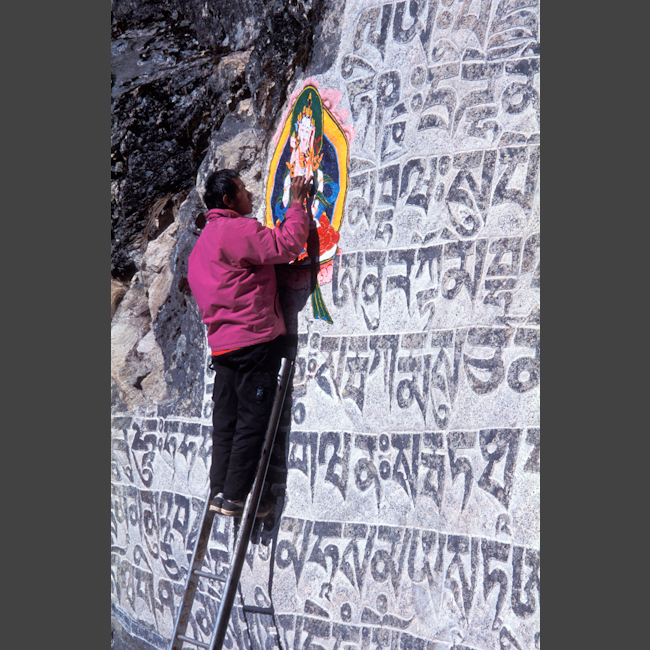

That afternoon we were happy to walk without packs and hiked up to the Thubten Choling monastery a few miles away. An unusual harmony of “clink, clink, clink” sounds could be heard as we approached. We soon discovered stonemason monks created this noise by chiseling stones into perfect square blocks by hand with intense concentration: When we came into view they suddenly stopped to stare at us. This monastery was founded by Tibetan Buddhists who escaped across the Himalayan Mountains when the Chinese invaded, and a Tibetan monk guided us through the interior of the old but well-preserved buildings. Ornate Thongkas – spiritual paintings with a patterned silk fabric border – and other religious artifacts were displayed around the room, which we enjoyed until the monk tried to sell us a beaded necklace at an outrageous price. Somewhat jaded we declined the necklace but left the expected donation and returned to the comforts of Junebesi for our second night.

Day 8: Ringmo

The next section of the trail was especially easy and the rest day in Junebesi had restored our bodies. Walking along a smooth nearly flat path gave us the opportunity to gawk at the scenery and talk to each other – something I rarely had the breath to do. At noon we rounded a corner and were rewarded with our first view of Mt. Everest; it’s top peeked above among the many surrounding 25,000-foot plus snowcapped mountains. These giants were impressive but distant – we still had a long way to go to reach base camp. After a few pictures we leisurely ate a lunch of milk tea and yak cheese (a local specialty) outside on the patio of the Everest View Lodge. Further along the tail a little boy walked with us for a while, spontaneously smiling and handing me freshly picked flowers. Another few hours of walking brought us to the town of Ringmo, and since the next major village with lodges was several hours away we decided to stop early for the day. “Oh why can’t everyday of trekking be as pleasant this?” we asked each other.

Day 9: Kharikhola

Yesterday we met a British newlywed couple traveling with a porter and a British trekker they teamed up with in Jiri – today we decided to walk with them since they stayed at the same lodge & were heading to the same town. However I was frustrated trying to keep up with trekkers carrying little more than a small daypack. I thought how easy it would be if we just piled our packs on top of their porter’s load. But then we’d lose the satisfaction of knowing we could complete this trek on our own, and we didn’t have enough extra cash to pay for a porter anyway. Somehow we managed to keep up with the British trio while walking down 6,000 feet to cross a river at the bottom of the valley then continuing up the other side for another 2,000 feet. After eight hours of continuous trekking we reached Kharikhola exhausted and sweaty; we quickly cooled off after a lukewarm shower in the stone hut next to our lodge. The five of us were the only guests in the cute Sherpa lodge and we all turned in early. Regardless how tired we were it was still strange to got to bed at 7 p.m.!

Day 10: Chutok La Pass

During breakfast we witnessed a startling spectacle; suddenly the British newlywed began moaning and clutching his stomach complaining of sharp pains. His discomfort mysteriously continued to intensify until he rushed to the bathroom & passed a kidney stone! The nearest airport was at Lukla – a long day hike away – and the nearest doctor was even further; in his condition it would have been impossible for him to ride a horse to these locations anyway. We gave him some of our strong prescription painkillers (left over from Dale’s last surgery), which helped him a bit. His wife had passed kidney stones herself last year so at least they knew what to expect . . . he just had to drink lots of water and let nature take its course. It was a very inconvenient place to fall seriously ill – we knocked on wood to remain healthy.

We pushed hard for another long day in order to remain on schedule for a few rest/ acclimatization days in Namche. On this portion of the trail our guidebook warned of “demoralizing false summits”; indeed every time we reached a ridge top thinking we’d made it to the end of the climb yet another taller hill loomed ahead. Finally at 5 p.m. we stopped at the top of Chutok La Pass (9,121 feet) at a small house perched alone on a steep cliff side.

Even though most of the lodges we’d stayed in so far had been quite rustic (loose stone exteriors with little insulation, flimsy plywood floors and walls, thin foam mattresses on top of a hard wood block bed frame, with an outhouse bathroom), I wouldn’t have traded any western comfort for the incredible vistas. Lying in bed at the cliff-side lodge I could peer out the window inches from my head down 5,000 feet into the valley below and 10,000 feet above to the beginning of the Himalayan Mountains. Most mornings I awoke at sunrise to watch the first rays of golden light touch the surrounding peaks then creep slowly down to the foothills. It’s hard to picture a more inspiring sight.

Day 11: Phakding

This morning we woke to the clanging of bells from water buffalos lumbering unsteadily down the treacherous rocky trail below. Soon after beginning the same descent ourselves, we caught up with this group and discovered what happens to the unlucky water buffalo that stumbles off the steep trail. The porters had already ‘sacrificed’ the poor beast and were busy skinning and butchering it’s remains to sell at the weekend Namche market. We later saw a porter carrying huge cuts of meat that overflowed his basket –the exposed meat was baking in the intense high altitude sun and the stench attracted dozens of flies. We vowed to be vegetarians while in Nepal.

PHOTOs: skinning water buffalo, porter carrying meat (scan)

When we reached the junction where our trail from Jiri merged with the trail from Lukla, everything abruptly changed. We were startled to see freshly groomed tourists in their pressed & matching clothes who had just stepped off the airplane and were strolling along the trail with a line of porters following. Huge package tours clogged our path ahead, their clients panting unaccustomed to the thin high altitude air they had been dropped into. Until this point in our trek, everyone on the trail always greeted each other with a friendly “namaste” as they passed; now the whole atmosphere was different and most people were either too rushed or preoccupied to even make eye contact. When we sat down for lunch we were in for another shock – prices for everything had tripled. Together we had easily survived on less than $15 U.S. dollars a day beforehand – most rooms only cost 20 to 50 U.S. cents per night and meals rarely cost more than a couple of dollars. Now a can of Coca Cola was $1.75 U.S. dollars!

Phakding, halfway between Lukla and Namche, is the common first night stop for tour groups that have just flown in from Kathmandu. We also stopped here because we were tired and Raaj had recommended a lodge, which was nice though crowded. We took a cool shower and tried to warn a group of Japanese women that the ‘hot’ shower would be a different experience than they were expecting. They proceeded anyway and reappeared soon shivering. We watched as the women drank huge pots of hot tea to warm up, dreading the inevitable result: they spent most of the night thumping in their new hiking boots down the hallway between their rooms and the communal toilet, continuously waking us up. Whenever possible afterwards we searched for the least crowded accommodation.

Day 12 & 13: Namche

Namche – a city in the middle of the Himalayan oasis. We were excited to be approaching it’s bakeries and the 15-minute scorching hot showers other trekkers raved about. Just one thing stood in our way – a long climb of several thousand feet. The final hill took longer than expected since I was running on ‘empty’ – the hard boiled eggs we’d ordered at breakfast & carried with us for lunch turned out to be barely cooked thus inedible. A chocolate bar and thoughts of hot fresh cinnamon rolls were just enough inspiration to get me to the top.

The leader of a trekking company we met earlier had recommended a nice hotel so we headed there in hopes of finding a quiet spot to rest for a few days. We mentioned this contact and it’s a good thing we did since all the budget rooms were full. So as to not disappoint their friend, they gave us a $15 U.S. dollar deluxe room for the same price as their budget room – $3 U.S. dollars. Our room was carpeted, the beds had new thick mattresses and warm blankets, and an attached bathroom with a western toilet, sink, & hot shower – oh the luxuries were appreciated! Best of all the place was super quiet -since it was expensive it was not popular with most trekkers. The first thing we did was wash our filthy socks in the hot water from the sink. Then we pigged out on freshly baked goods – our favorites were the cinnamon-apple strudel and peanut pecan cookies. At our hotel we ate pizza for dinner and at breakfast we feasted on canned orange juice, coffee, hash browns, scrambled eggs, and toast. We washed our remaining dirty clothes in the sink the next day & still had enough hot water left for a long shower. For most of our second day in Namche we just sat and baked in the sun alongside our clothes. The only walking we did was to the nearby stores to rent down jackets, buy thick yak wool socks for lounging around the drafty lodges, and to stock up on a hefty supply of snickers bars for the toughest section of the trail ahead.

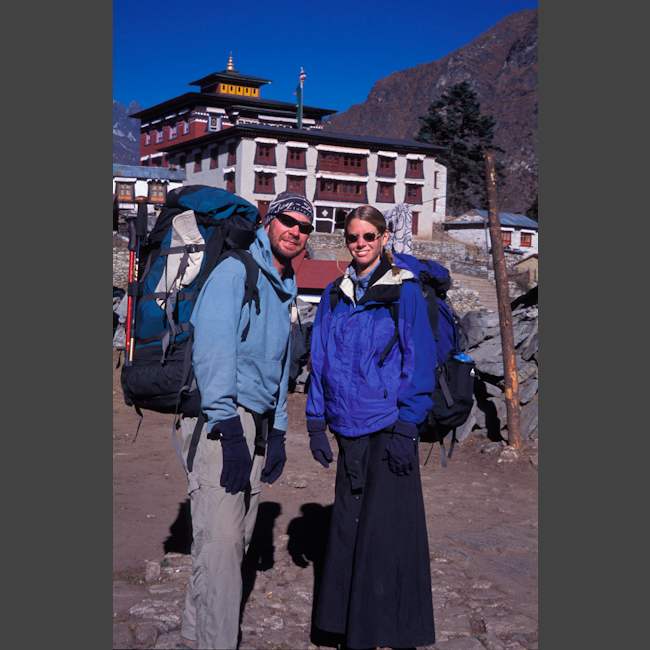

Day 14: Tengboche

We left Namche late in the morning; our next stop was only a half-day away so there was no need to rush. In fact we could see the Tengboche monastery – our next destination – almost immediately after leaving Namche, so we assumed it would be an easy hike. As a bird flies the distance was short, but another grueling valley & river had to be crossed before reaching Tengnoche, 12,664 feet. The monastery & lodges were perched on top of a ridge with spectacular mountain views on either side. Unfortunately everyone likes to stay here to admire these views so area was packed with tents from tour groups and lodges were nearly full – we got the last available room. From our bed we could look out the window at an unobstructed view of the Himalayan Mountains; the next morning I awoke just in time to see the sunlight touch the highest peak. I rushed outside to take photos of the scenery & was rewarded with another delight – the chants of monks echoing down from an open window of the monastery. Even Dale roused out of bed at this early hour to watch the monks clang cymbals and blow long low-resonating horns, their ritual morning wake up call performed minutes after sunrise to announce the beginning of their dawn prayer session. The Tengboche Monastery was built as a secret place of solitude hidden in the mountains; although now it is touristy it’s still possible to experience its peace if you’re willing to make an effort to escape the crowds.

Day 15: Pangboche

After enjoying watching & listening to the monks perform their morning music at the monastery we slowly warmed up with milk tea & a hearty breakfast. The remainder of our ascent to Everest Base Camp would be at a slower pace, so there was no need to rush off in the freezing early morning temperatures. In order to avoid getting a potentially fatal case of altitude sickness, once above 12,000 feet we never ascended to sleep at an altitude higher than 1500 feet from where we were the night before. Half-day hikes were a welcome relief from the long 8-hour days we’d spent on the trail most days the previous week.

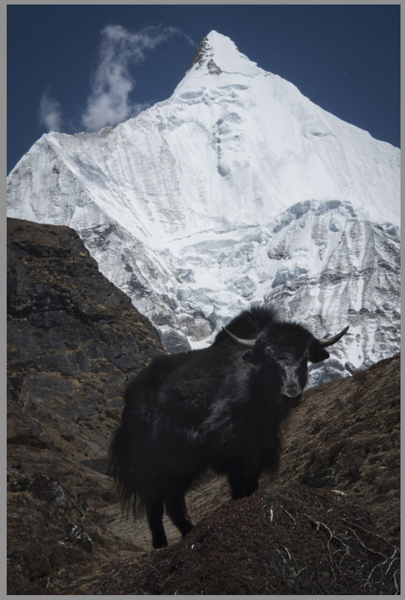

We reached Pangboche, 13,123 feet, by noon – in time to enjoy a snack in our lodge’s large warm sunroom overlooking Ama Dablam, a peak many say is the most gracefully shaped of all the Himalayas. This village is the highest village in Nepal that has been traditionally occupied year round – other settlements further up the trail were previous summer yak herding stations that were only recently converted into lodges for tourists heading to Mt. Everest.

The owners of Sherpa Village Resort, our well-appointed lodge, told us that we had arrived in Pangboche on a special day. The lama from Tengboche monastery had traveled to their monastery, the oldest in the Khumbu region, in order to perform blessings. Since the owners were headed to the monastery themselves we were invited to come along to witness the spectacle. We struggled to keep up with the fast pace of our fit Sherpa hosts; Nepalese people always take the most direct route possible, which in this case was a steep climb of a couple hundred feet straight up the hillside. When we arrived, gasping for breath in the thin air, it seemed that the entire village was stuffed into a small courtyard at the Pangboche monastery. More Buddhists stood on the balconies above dressed in their ceremonial clothes, overflowing the path leading to the lama. One by one everyone lined up to give their donation to the lama, and were in turn blessed when he placed a white ceremonial scarf around their necks. The atmosphere was charged with a festive air and we were impressed that in less than an hour several hundred villagers managed to squeeze their way through the passageways of the old building to reach the lama without creating chaos.

Photo: Pangboche blessing ceremony

Late that evening (9 p.m. was past our normal Nepal bedtime) we found ourselves caught up in stories we milked from Ang Sherpa, the owner of our lodge. We began our conversation with questions about the scenic photos on the wall and Ang revealed an impressive history of mountaineering feats that had made him somewhat famous. In 1991 he was part of the only all Sherpa ascent of Mt. Everest. He was one of three Sherpas who made it to the top – it was aparticularly difficult year to summit due to the deep snow and uncooperative weather. National Geographic covered the story in its March 1992 edition, titled “Guardians of the Himalayas” and featured a photo with Ang at the top of Mt. Everest. Humble and unassuming, Ang’s character exemplified the spirit of the Sherpa people we had traveled so far to encounter.

Photos: Ang & wife holding national geographic magazine

Day 16 & 17: Dingboche

A pleasant walk along a roaring river brought us to Dingboche, 14,271 feet, in just a few hours. We were lucky to get the last room in the Snow Lion Lodge, a popular spot many Sherpas had recommended. It’s a good thing I encouraged Dale to race ahead up a hill (I was always slow climbing) to pass a group of people heading to the same place.

We spent two nights in this village in order to properly acclimatize. On our ‘rest’ day we decided to climb the nearby Nangkartshang Peak described by our guidebook as a “half day excursion that offers some of the best views in the region”. Little did we know that the summit was more than a 3,000-foot climb straight up a slippery slope. About 500 feet short of the summit we gave up climbing since the afternoon fog had already rolled up from the valley below and would soon engulf us. We enjoyed a peanut butter & jelly sandwich and a view that made it seem like we were on top of the world – only the peaks of the highest surrounding mountains poked up above the clouds.

Photos: Dale eating PB&J sandwich near top of Nangkartshang Peak, view of snow lion lodge from stupa

Luckily we had washed our socks, underwear, faces, and hair in a bucket of hot water from the kitchen earlier that day. We didn’t realize how long it would be before we would have this opportunity again . . .

Day 18: Thukla

We decided to stop next in the tiny and rarely visited settlement of Thukla (15,092 feet). There was only one other guests at the Yak Hotel – an interesting American named Doogle. At the age of 30 Doogle left a high paying consulting job in the corporate world , sold his house, car, and most of his belongings, and took off to travel around the world for a decade. He was in his seventh year of traveling when we met him and had many great stories to share. Our host, Tenzing Sherpa, had even more fascinating adventures. He has summitted 10 of the world’s 14 highest mountains (all over 25,000 feet) including K2, Mt. McKinley, Ama Dablam (his favorite) and Everest. However he recently gave up mountaineering after climbing with Rob Hall on his ill-fated 1996 expedition (both guides & several clients died when they were caught in a storm on shortly after summitting). For obvious reasons he doesn’t like to talk about this Everest tragedy, but he did share a few details of previous Everest summits. We were amazed to find out that when Tenzig was near the summit, he boiled hot water and poured it immediately into his insulated water bottle then placed the bottle next to his body wrapped up in minus 30 degree Fahrenheit sleeping bag, it froze solid within just 2 hours. He had to wake up to boil more water several times each night. It wasn’t until later on during our trek, when we read John Krakauer’s book “Into Thin Air” about the 1996 Everest disaster, that we discovered that Tenzing fell into a crevasse near Everest Base Camp and was pulled up several hundred feet with a broken leg. This accident probably saved his life since he was unable to complete the expedition.

One of the most amazing aspects about traveling in Nepal was the people we encountered leading everyday lives doing what most would consider extraordinary feats. The average porter, considered in Nepal as one of the lowest caste groups, carried incredible loads over immense distances of rough high altitude terrain using dokos (traditional v shaped wooden baskets supported only by a trumpline head strap) and wearing flip flop shoes. Most of their loads weighed in excess of 200 lbs and consisted of many bulky items such as full sized folding tables and chairs, sacks of rice, and large flat pieces of plywood that caught the wind. I wanted Dale to try carrying a porter’s load for a photo, but he was afraid that he’d strain his neck – even the smallest load carried by porters as young as 12 weighed more than 50 lbs. Most porters were shy & didn’t like getting their photograph taken, though we were able to capture a few photos unnoticed soon after leaving Thukla.

Day 19: Lobuch

Lobuche (16,207 feet) is considered a ‘hell hole’ by most trekkers; it is cramped, filthy with garbage and smelly outhouses, and has no clean water supply. Many trekkers get sick here due to these unsanitary conditions – indeed my stomach was acting up again from bad bacteria in something I ate. To get away from the hordes of trekkers crammed in the few lodges, we slept in a tent – it was a memorable experience & probably the highest altitude camping we’ll ever do. We were provided with thick mattresses and blankets and we stayed warm by snuggling deep in our down sleeping bags, heads covered by our hoods, until ‘nature’s call’ woke us.

Easily relieving ‘nature’s call’ is something we’d always taken for granted – in Nepal it’s altogether a different experience. First of all, in high altitudes it’s essential to drink large quantities of water to avoid dehydration. Secondly, to combat altitude sickness your kidneys process liquids faster, which result in increased urination. Our guidebook said it was a good sign to pee once during the night, and in fact we often had go more often. One British trekker joked with us that he wanted to wear diapers at night to avoid the necessity of leaving the warmth of his sleeping bag to venture outside in the subzero temperatures. Everyone dreads the midnight trip to the outside toilet – it’s a hassle getting dressed, putting on your hiking boots, searching for a flashlight & toilet paper, then squatting in the outhouse trying not to step on puddles of frozen urine near the edges of the hole for fear that you’ll slip in. It’s an inner struggle of denial – “Maybe the urge to pee will pass if I can fall asleep”, you think, but it never does.

The next day I still didn’t feel well but decided to push on – we didn’t want to spend any more time in Lobuche than absolutely necessary.

Day 20: Gorak Shep

After a tiring scramble along a glacier’s moraine trail (the undulating gravel & boulder surface made walking difficult) we arrived at Nepal’s highest altitude settlement – Gorak Shep – at nearly 17,000 feet. The facilities here were much better than in Lobuche, and the Himalayan Lodge we stayed at was nice. It was Dale’s Mom’s birthday, and we were worried about the difficulties she has suffered from chemotherapy to battle cancer. So after dropping off our packs at the lodge we continued up to the summit of Kala Pattar to place a prayer flag in her honor. Climbing to the highest point of Kala Pattar takes most people one and a half to two hours; it took us nearly two and a half hours and I literally crawled on my hands & knees over huge precarious boulders for the final 200 yards. We made it to the top, 18,300 feet, just in time to witness one of the most spectacular sunsets we’ve ever seen. Mt. Everest, at 29,000 feet, is the highest peak in the world thus is the last point on earth to catch sunrays. It’s nearly snowless face turned a deep shade of red just as the sun dipped below the horizon. After sunset all the snow-capped peaks glowed soft pastel colors and a quarter moon illuminated our way back down to Gorak Shep.

Surprisingly most trekkers only pass through Gorak Shep on their way to & from Kala Pattar, so our sunset view would be impossible for them to witness. For the first time we felt the effects of altitude sickness – we both got splitting headaches & became dizzy after descending Kala Pattar. These symptoms, compounded by my weakness from my recent bout of travelers diarrhea, left me helpless to do much else other than go to bed early for an restless night attempting to sleep.

Day 21: Gorak Shep, aka Day 2 of our Base camp

In the morning I was distressed to find that my condition had worsened – I scratched my cornea overnight when trying to remove an uncomfortable contact. I wore my airplane sleep mask over both eyes since sunlight was unbearable, and spent all day in the lodge resting, sleeping, and eating Tibetan bread spread thick with honey. At 17,000 feet your body uses considerably more energy to simply breathe. Out guidebook states, “Every trekker will experience some or all of the following normal symptoms at altitudes higher than 14,000 feet: periods of sleeplessness, the need for more sleep than normal – often 10 hours or more, occasional loss of appetite, vivid wild dreams, unexpected momentary loss of breath, periodic breathing that will occasionally wake you while sleeping, the need to catch your breath frequently while trekking, runny nose, and last but not least increased urination.” We took turns experiencing all these symptoms.

Day 22: aka Day 3 of our Gorak Shep Base Camp

This morning I felt slightly better, although my eye was still tender & vision blurry, so we decided on just walking a short distance to see the Everest memorials. Our search for a peaceful place to put a prayer flag for my Uncle who had passed away recently and for a family friend fighting cancer ended here. Buddhists believe that by hanging prayer flags – pieces of multi-colored cloth with religious inscriptions – high in the mountains your prayers will be carried towards heaven each time the wind flaps the flags.

Day 23: aka Day 4 of our Gorak Shep Base Camp

I tried wearing my right contact again last night – a big mistake. I discovered that everything takes longer to heal at high altitudes, including my cornea, so we were forced to stay inside the lodge for yet another day. I was beginning to relate to the stories I’d heard of expedition members being stuck at base camp for days on end due to bad weather or a physical ailment. At least our base camp was relatively comfortable with many friendly trekkers. One American couple was celebrating their 60th birthdays on this trek, proving to us that adventure travel doesn’t have to end when you get older. The most entertaining people to watch were those venturing away from tropical climates for the first time; groups from Singapore and Barbados were especially shocked by the cold weather. By far the most captivating character we met was the ‘flag man’, a Bulgarian who has walked across all six continents. Recently he walked from the southern tip of India all the way across the Nepal border & up to Gorak Shep, where we met him; during this time he never once took any other form of transportation. An environmentalist & advocate of world peace, he walked with a backpack supporting a full sized Bulgarian peace flag to promote these causes in the far corners of the earth. We met more long-term travelers while trekking in Nepal than anywhere else on our journey; in fact to many we were the short-term travelers.

Day 24: aka Day 5 of our Gorak Shep Base Camp

Today we both felt good enough for the 5 hour round trip walk to the ‘real’ Everest Base Camp – elevation 17,500 feet – a few miles away. This trek was different from any walking we’d done previously – we gingerly stepped on the glacier’s surface covering of loose gravel & rocks which were coated in ice. There were no expeditions camped here when we arrived (the season to summit Everest is March-May or Sept-Oct) but we were able to figure out its approximate location by spotting a few remaining tent tarps. Sitting on the glacier enjoying a snickers bar we saw several avalanches & could actually hear the groans & creaks from the glacier slowly moving beneath us. Our days of waiting finally had paid off – the weather was relatively mild & wind was calm. Most people who trek to the top of Kala Pattar don’t take the extra time to stay & visit Everest Base Camp, which is a shame. For us it was the culmination of this trek, and in fact the last new destination we’d reach before returning home from our 14-month journey.

Day 25: aka Day 6 of our Gorak Shep Base Camp

Feeling stronger, we decided to head up to the top of Kala Pattar once again. This time we left earlier – at 12 pm – and made it to the top in one and a half hours. We still had to pause every so often to catch our breath, but after spending a week at 17,000 feet we were finally fully acclimatized. We spent several hours at the top in quiet solitude, taking photos and enjoying the majestic view before heading back down.

Day 26: aka Day 7 at our Gorak Shep Base Camp

I think we were some of the longest staying guests that season at the Himalayan Lodge and we were sad to say goodbye. The Sherpa owner, who we called Didi (meaning sister in Nepalese), had taken care of us & cooked many surprising meals including pizza in her dirt floor kitchen. Heading down was much easier; we made it to the Snow Lion Lodge in Dingboche in just 5 hours – it had taken us 3 days to cover this same distance going up.

Day 27: Tengboche

We didn’t see the Buddhists morning prayer session at the monestary when we stayed in Tengboche on the way up to Kala Pattar, so on our second visit to this village I was determined witness this ritual. We rose at 6 am, dressed in our warmest clothes, and entered the monastery. We were the only westerners; we sat huddled on a thin mat on the wood floor shivering in the unheated prayer room as we watched the monks chanting and playing ceremonial instruments. The Buddhist emphasis on meditation was effective; though most monks were only wrapped in a thin cloth red robe & some were even barefoot, they seemed impervious to the cold.

Day 28, 29, & 30: Namche

It had been two weeks since we washed our hair in the hot water bucket at Dingboche, and 16 days since we had a full shower in Namche. How could we bear to go so long without bathing? At 17,000 feet not only did most water quickly freeze in the unheated lodges but even if we could have managed to heat enough water to clean off the dust from the trail we certainly didn’t want to undress from our many layers of warm clothing. Dale had even gone so far as to grow a beard – he looked like a mountain man. Back at the same lodge we stayed at in Namche before, we took glorious hot showers & couldn’t remember a time when getting clean felt so good! We spent three days in Namche doing nothing other than gorging on bakery goodies, sitting in the sun reading, and just relaxing.

Day 31: Bemkar

On our last night on the trail before reaching our departure point in the city of Lukla, we chose to stay overnight at the infrequently explored town of Bemkar. The peak of the trekking season was now over and we were the only guests at this friendly Sherpa lodge. For dinner we ate the best Sherpa stew we’d encountered and enjoyed the tranquility of the location.

PHOTO: lodge at Bemkar

Day 32: Lukla

After a month of trekking in Nepal, I finally found walking anything other than a steep hill effortless. A strange sensation overcame me while walking on this last section of trail. Maybe my perceptions were altered because I was coming down with a cold; my head felt oddly separate from my body. Each stride I took fell into a rhythm – indeed I found it easier to keep moving than to stop, my legs walked without any conscious thought.

I was reminded of a few books I had read previously. In a story from the Travelers Tale series for Nepal called “The art of walking” the author writes, “In such a demanding environment, Nepalis early on acquire a graceful, efficient, and mindful walking style” and continues by describing a Nepali porter who “. . . covered ground like flowing water. He eased effortlessness from step to step, moving as smoothly as if on an escalator”. Peter Mathiessen, in his book “The Snow Leopard”, reinforces this description of the Nepalis grace as an “eerie trance state . . .(Nepalis) glide along with uncanny swiftness and certainty.”

Day 33: Katmandu

We flew out of Lukla on one of the most incredible runways we’d ever seen. It was short & sloped steeply; on takeoff we became airborne just as the runway abruptly dropped out from underneath us into a deep valley. In forty-five minutes we covered the same distance it had taken us 12 days to walk. Looking down at the deep gorges and valleys we’d traversed on the way up we were impressed with what we had accomplished. When we returned to Katmandu on December 5th we noticed that winter had even reached the lower elevations – it was noticeably cooler than before and far less crowded.

Trekking in Nepal was one of our more difficult challenges of our travels, made all the more worthwhile by our efforts to make it on our own. In the cool mountain air and inspiring vistas we were able to clear our heads to reflect on our journey. In a short story titled “The awkward question”, Paul Thoreau asks other adventurers why they feel compelled to complete arduous endeavors. One answer best sums up our Nepal exerience:

“ . . . such an effort was as much esthetic as athletic. And that the greatest travel always contains within it seeds of a spiritual quest, or else what’s the point?”

Sabah

Our 10-day Sabah Saga

There’s one travel truth I should have learned by now: if you plan an inflexible itinerary something will always happen to put a kink in it. Dale and I only had a 10 day layover in Sabah, so upon arriving in the capital city of Kota Kinabalu we planned to make the most efficient use of our time by booking a series of discounted, non-refundable tours. Included was a scuba dive lodging & meal package on the island resort of Sipidan, reservations at a jungle lodge to visit a orangutan rehabilitation center, and permits to climb Mt. Kinabalu, a 13,000 foot volcano. I knew it would be a grueling schedule even under ideal circumstances, but certainly hadn’t planned on the additional challenges of getting Dengue Fever, a scratched cornea, a cold, and my toenail falling off!

My misfortune began our first evening in Sabah. After finishing our bookings, I began to feel queasy and tried to go to sleep early. That night I was surprised by how quickly & violently tropical illnesses take root. By 2 a.m. it was undeniable that the horrible throbbing in my head and aching of my body wasn’t just caused by the loud music vibrating our hostel room from the karaoke bar below. At first I thought I was coming down with a nasty case of the flu, but I had to admit my symptoms matched the definition of Dengue fever stated in the Lonely Planet’s “Healthy Travel Asia” book:

“The illness usually starts quite suddenly with fever, headache, nausea and vomiting, and joint and muscle pains. The aches and pains can be severe…and many travelers report experiencing extreme tiredness with muscle wasting and lack of energy for several weeks…”

Those pesky mosquito bites I got in Manila turned out to be more of a pain than I ever imagined.

I was determined to regain my health quickly since our tours couldn’t be postponed for long.. After two days rest I convinced myself I was on the mend when the second incident happened. I woke in the middle of the night, this time to a piercing pain in my eye – debris had slipped under my contact and scratched my cornea. When we really couldn’t delay our trip to Sipidan any longer Dale led me, a weak hobbling ‘pirate’ with a patch over my eye, on our long journey to the island.

Scuba divers have voted Sipidan as “the best beach dive in the world” and we agree. Only 45 feet from shore the reef drops off dramatically from 9 to 90 feet. From the Borneo Diver’s pier you can sit and watch sharks and turtles lazily swim through the clear shallow water covering the reef directly underneath. After another day of rest I was well enough to join Dale on a few of the boat dives and was not disappointed for my efforts. The most unusual aspect of these dives was the amazing amount of turtles we saw on a consistent basis. They often allowed us to approach closely; we were dwarfed by their size and amazed how gracefully an 80-year-old specimen could swim.

Back on Borneo, traveling up the eastern Sabah coastline proved to be another adventure. No deluxe air-conditioned buses were available so we rode as the locals do – on a converted minivan. Its original seats had been stripped and replaced with rows of closely placed benches. Our vehicle, which regularly seated six passengers, was crammed with 12 adults and 6 kids. Luckily our large backpacks were allowed on since they provided extra seats in the isle. Besides the occasional screams from the babies and men who constantly puffed away on their cigarettes, everyone was amazingly calm – even we managed to stay still squeezed in our tiny space like accordions.

Upon reaching our next destination we were relieved to discover the room we pre-booked was in a quiet, spacious lodge at the edge of the jungle. The orangutan feeding platform at the rehabilitation center was a pleasant fifteen-minute walk through virgin forest. By the afternoon the tour buses had departed leaving more orangutans than people in the preserve. Two friendly male orangutans found Dale especially entertaining. Although we tried not to disturb them in their habitat they quickly approached us and attached themselves to Dale like a long lost relative.

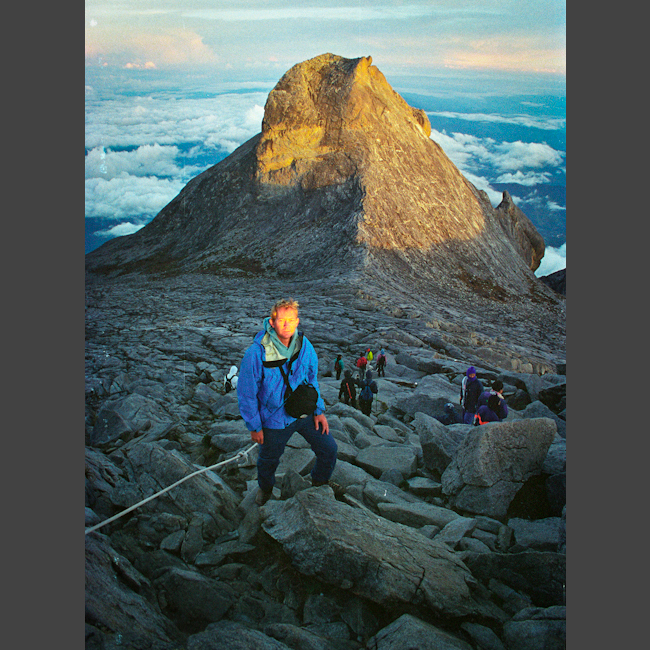

By the time we reached Mt. Kinabalu I’d regained my health if not my strength. Since climbing this volcano is the number one tourist attraction in Sabah, I thought, “How hard can it be?” At our dorm room in the hostel we met other like-minded hikers and decided to team up with four of them to share the cost of the required guide. We woke early the next morning to prepare for a long days. It was distinctively cooler at the base of the mountain (3,000 feet elevation), so we dressed in pants, long sleeved shirts, and wore shoes for the first time in five months. Although my nose began to dribble with this sudden climate change we welcomed the cool air since we began to sweat just 15 minutes into the hike. The first day of hiking was all uphill, ascending 6,000 feet through sub tropic, temperate, and alpine regions. The trail was well trodden with occasional handrails and 2,500 man made steps spaced along the more difficult sections, but I couldn’t help but think, “This is the Stairmaster from hell!”

Harry, our patient Malaysian guide, was required to stay with the slowest member of the group (me) and Dale kept the same pace weighed down with carrying both our daily supplies in one pack. Six hours after beginning we struggled into the mid mountain lodge, our final destination for the day. We collapsed in the dining room, drank hot tea, and enjoyed impressive views as mist drifted apart to reveal glimpses of the valley far below and imposing granite towers near the summit. Not only could I barely move, but also I regrettably resigned myself to acknowledging – you guessed it – that I was sick again, this time with a cold.

For the non-acclimatized it is difficult to sleep at high elevations. We arose the next morning at 2 a.m. after a night of restless sleep to continue up to the summit in time to watch the sunrise. The final 4,000 feet was by far the steepest and most treacherous section of the trail and we climbed with just our headlamps and the full moon to illuminate the way. Dale was doubtful that I would make it to the top in my condition, and I’m sure Harry agreed but was too polite to say anything. When we reached a section of seemingly endless granite boulders so sheer that we had to grab ropes bolted to the rock in order to scramble up their faces, I began to wonder myself if I’d succeed. At 5 am we reached the top of a peak that allowed us to finally see the summit above – that view was the inspiration I needed. By 5:45 a.m. we reached the summit just in time to watch a spectacular sunrise.

Most people believe that climbing down a mountain is far easier than going up, but I had my reservations about descending 10,000 feet with my already wobbly legs. We stopped for a hearty breakfast back at the mid mountain lodge at 9 a.m., grabbed our pack, and continued down. Marathon athletes compete in an eco-challenge race every September, jogging up and running down this volcano trail to complete the entire circuit as quickly as two hours forty-five minutes. For us, it took nearly as long to descend as ascend.

For the last three hours we walked in a complete downpour, and when the trail transformed into a muddy river it didn’t help quicken our progress. By the time we reached the bottom our leg muscles were like spaghetti and we couldn’t bare the sight of any steps, up or down! I lost one toenail, and Dale lost two along with his desire to hike anything else for the rest of our trip. Myself? I think our toenails will grow back by October, just in time to see what the Himalayas might have in store for us.