No air-conditioning, tinted windows, radio/ tape player, or shocks. Sunshine, our faded-yellow ’83 Subaru wagon, labored down the outback highway fairing just slightly better than us in the oppressive heat. We drove 12 hours a day for 3 days straight, over 1,200 miles from Townsville on the Queensland coast to Alice Springs in the center of Australia, stopping only for fuel and food at gas stations. The sun, a merciless blinding orb, relentlessly shone into the car with a surprising intensity. After the first day of driving we actually longed for a cooling rain, which continued to haunt us relentlessly during our journey.

The outback highways are ruled by wildlife and road trains. At sunrise we began driving just as the lizards awoke to bake on the bitumen and the birds of prey swooped down to feed on last night’s road kill of kangaroos and cows. Hawks stood two feet tall on legs thick as a man’s forearm and glared at us from the roadside as we drove by. Lorikeets (rainbow colored parrots) played ‘chicken’ with our car, flying alongside and darting in front of & behind us. Other birds hadn’t mastered this dance & dive-bombed our car – we hit a few despite our attempts to avert their death wish. One time we dared to drive at night when it became even more apparent we were travelling through wild land. Kangaroos, who hid in the shade during daylight, suddenly leapt at out from the bush and hopped across the road in front of our headlights. Most roads passed through unfenced grazing areas so we were accustomed to seeing cows on the roadside & the occasional herds crossing in front of us. In the dark, however, cows simply stood in the middle of the road and stared into our headlights. We nearly collided with one after cresting a small hill; it never budged as we screeched to a halt, honking madly. Road trains (big trucks with 3-5 trailers totalling 300 feet) also impeded our progress. At times the main highway was only wide enough for one vehicle, so each time we encountered a road train we wisely ‘gave way’, which left us coughing and blinded by a swirling cloud of red dust from the soft shoulder.

The isolation of the outback is hard to describe to anyone who hasn’t travelled there for an extended period of time. Often the road stretched out in front of us, straight and flat, with no signs of human inhabitation for distances as far as we could see. Many of the lands we passed were Aboriginal reserves: If the Aborigines had returned to this land they left no apparent tracks. Few people can withstand the harshness of this climate – our car thermometer often reached 115 degrees Fahrenheit, which felt almost unbearable as our sweaty bodies stuck to the vinyl car seats.

Since we only had two weeks to spend in the outback we sped to and from our destinations in the center as quickly as possible. When we did take the time to slow down for the night we found little used dirt roads to drive down and pitch our tent. After sunset we noticed sounds and sights we never would elsewhere. At first the silence was eerie and we both complained of a ringing sound in our ears (was this ringing always there in the background, but we had never noticed it before?). Then we began to notice small noises, such as the beating wings of a moth flying overhead. Occasionally we were unlucky enough to share our campsite with mozzies (aka mosquitoes); their buzz seemed so loud it sounded like we were being attacked by B-52 bomber planes. Most nights were clear and moonless and the southern sky lit up with a brilliant display of stars. The sky was so free of light pollution that the beginning and end of the Milky Way was clearly visible, and on several occasions we saw the entire trail of shooting stars streak across the sky. The Southern Cross was easy to spot along with Mars, the small but bright bluish-green Jupiter, and golden Venus. Each morning we awoke to the singing of birds and saw the stars disappear into the colors of the sunrise.

As we approached Alice Springs the rain began to chase us, making us curse our earlier wish. Roads became overflowed with newly formed rivers, causing us to stop at each flooded area to wade across and test the depth before proceeding. Unseasonably high rainfall was forecast for the next several days, so we decided to continue driving to the opal town of Coober Pedy, one of the driest spots in Australia. We would then work our way back up to Alice Springs via Uluru, the Olgas, and Kings Canyon, driving the back roads. Actually we were happy to continue driving – the outback literally and figuratively had gotten into our skin and we weren’t ready to wash it off and return to the city.

Several science fiction movies have been filmed in Coober Pedy, and it became apparent why as soon as we entered town. The desolate, lunar-type landscape looked like it was from the scene of post atomic battlefield. Old rusted cars, trucks, and mining equipment were strewn about, showcased as art for tourists to view; the flat, dry and dusty land was spotted with mounds of pink earth piled high next to the countless opal mines; and the majority of the town’s residents lived and worked in underground buildings dug into the hills. Our long journey to reach this destination felt oddly justified; we came to the outback to experience something different and were surrounded by bizarre human and natural landscapes.

It is not uncommon for temperatures to soar upwards of 120 degrees F during the Dec-Feb summer months, yet in March we enjoyed the coolest weather we’d encountered in Australia. Days were pleasant with low humidity and 75 degrees F highs, and evenings were cool enough for a sweater, which hardly made it necessary to remain underground. Nevertheless, we enjoyed the novelty of our underground hostel accommodation and drinking beers with the bartender while watching the movie “Mad Max”. When we did venture outside it was easy to walk everywhere – we covered most of the town in about an hour. An old fashioned mine tour was a fun excursion where we stooped through tunnels to see opal seams exposed in the sandstone and displays of how opal was originally mined in early 1900’s. Afterwards, we opted for modern opal viewing – shopping at the dozens of opal outlets. I was looking for a bracelet to fit my small wrist, so a helpful Aussie recommended the custom jewellery makers at the Opal Cutter. In about 2 hours (ok, I’m picky!) I had chosen the opals and designs for both a custom bracelet and pendant, and by the next day the jewellery was made – all at a very affordable price. That evening we celebrated my jewellery find over dinner at one of the many Greek restaurants in town. It was an interesting ambiance, divided between rowdy mine workers relaxing with a cold beer, locals enjoying the fine dining, and backpackers egging on ‘Crocodile Harry’ as he ranted in a drunken stupor.

The next day we decided to drive along a portion of the historic dog fence to the Breakaways Canyon. This fence is Australia’s equivalent to the Great Wall of China – it’s 3,300 miles long and was erected in the early 1900’s to protect farmer’s sheep and cattle from wild dingo dogs. We weren’t sure if this fence or simply the harsh climate kept away wild creatures – this stretch of desert was the most lifeless land we encountered. The stark landscape with its striking multi-colored sandstone canyon walls was the perfect backdrop for a remote campsite. We fell asleep without hearing a single mozzie and woke up to a silent dawn, the only time we’ve ever been camping and heard no singing/squawking birds in the morning.

Continuing on the Stuart Highway towards Uluru National Park, our anticipation of first glimpsing the monolith grew. Featured on the cover of most Aussie guidebooks, this immense mound of red rock juts up abruptly from the relatively flat landscape of the outback near the geographic center of the continent. The ‘red heart’ of Australia has long been an important spiritual center for the Aborigines and has more recently become a pilgrimage for worldwide travelers. Gradually the landscape changed from flat orange scrub to small undulating hills covered with more lush vegetation and red sandy dirt. Rounding a bend, we suddenly saw Uluru looming in the distance. Even through the rain the rock stood out – towering 1,141 feet tall and .2 miles wide – an impressive sight. As we approached its base the sky cleared and we were just in time to witness a spectacular sunset. Brilliant colors illuminated the remaining wispy clouds and as the last raysof sunlight passed over Uluru it was transformed into a series of red, orange, and pink hues until fading to grey.

Continuing on the Stuart Highway towards Uluru National Park, our anticipation of first glimpsing the monolith grew. Featured on the cover of most Aussie guidebooks, this immense mound of red rock juts up abruptly from the relatively flat landscape of the outback near the geographic center of the continent. The ‘red heart’ of Australia has long been an important spiritual center for the Aborigines and has more recently become a pilgrimage for worldwide travelers. Gradually the landscape changed from flat orange scrub to small undulating hills covered with more lush vegetation and red sandy dirt. Rounding a bend, we suddenly saw Uluru looming in the distance. Even through the rain the rock stood out – towering 1,141 feet tall and .2 miles wide – an impressive sight. As we approached its base the sky cleared and we were just in time to witness a spectacular sunset. Brilliant colors illuminated the remaining wispy clouds and as the last raysof sunlight passed over Uluru it was transformed into a series of red, orange, and pink hues until fading to grey.

The next morning we awoke early to watch sunrise and to visit the cultural center, which was packed with historical information about Uluru. We learned that when whites ‘discovered’ the Rock in the early 20th century they named it Ayers Rock and began marketing it as a tourist destination. Until recently most tourists visited simply to take photos of the sunset and to climb the steep, treacherous trail to the top. Then, fifteen years ago, ownership of the Rock was given back to the indigenous Anangu Aborigines, the name was changed back to the Aboriginal name Uluru, and joint management of the park between the Australian government and the Aborigines began. Now emphasis is placed on Uluru’s cultural significance, so we chose to take two tours and to walk the circumference of the base rather than to disrespect the sacredness of the rock by climbing it.

The Mala walk, our first guided tour, began at 8 a.m. and was led by an Australian ranger. She brought us along a trail at the base of Uluru to a tall, narrow canyon in the Rock, stopping along the way to decipher Aboriginal rock paintings and areas of spiritual importance. This section was known as the Wallaby Dreamtime place – from Aboriginal dream visions about the creation of this land and its resident animals. We continued walking around the base alone after this tour, a three-hour endeavor, and missed hearing the fun informative stories that previously brought the rock to life. So, at 3:30 p.m. we joined a second tour, the Mutitjulu walk to a permanent waterhole near the base. Charlie, our Aboriginal guide explained the dreamtime stories of the rainbow serpent and showed us natural reliefs in the Rock depicting a battle between snakes. Somebody asked Charlie why the Aborigines still allow Uluru to be climbed when it is against their beliefs. It was a difficult question but he managed to answer simply, replying that Aborigines are guardians of the land thus feel responsible and greatly saddened when somebody gets hurt. Additionally, we had previously been told that Uluru was only conditionally returned to the Aborigines – they initially were required to keep the trail to the top. To further complicate this issue, Aborigines are given a percentage of the profits from the park fees and climbing the Rock is a big draw for tourists. Nevertheless, the Aborigines are patient people who hope to educate visitors on the reasons why they should respect their wishes to not climb Uluru rather than igniting anger by forbidding this to be done. This approach has been effective – slowly but steadily the number of climbers has been decreasing.

Near Uluru are the equally spectacular sight of the Olgas (aka Kata Tjata ), composed of many boulder-like rocks stacked in a row, and Kings Canyon. It had been raining steadily for the past week so we were rewarded with a green, wild flower & billabong covered landscape – scenery most travelers don’t experience in the outback. Normally dry streambeds were active with fish, frogs, pollywogs and other animal life. Anyone who says the outback is a just harsh dry place has yet to visit after the rains. A roadside marker at a stream crossing showed a maximum depth of 2 feet, so we adopted the Aussie attitude of ‘giving it a go’; unfortunately a sputtering motor brought Sunshine to a halt midstream. When we stepped out to push volunteers were already wading out to help us to the other side. Fifteen minutes later, after drying out the distributor cap we continued on our way to Kings Canyon.

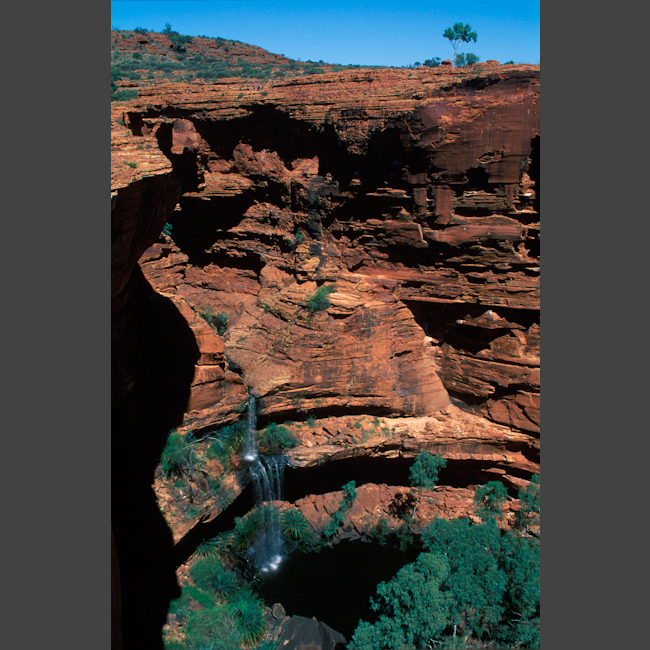

A spectacular red rock gorge including natural features such as clusters of domed outcrops, sheer canyon walls rising over 300 feet, and a lush palm oasis hiding high in the narrow gorge rewarded our efforts. The four-hour Kings Canyon rim walk offered fantastic views of the surrounding area, and half way along the walk the Garden of Eden came into view. The waterfall cascaded to the gorge floor creating a surreal oasis of unbelievable splendor. We enjoyed a cool and refreshing swim in the spring fed pools before walking back to our campsite.

The last leg of our outback road trip was the Mereenie Loop, a 4-wheel drive only dirt track that snakes through Aboriginal land, mountain ranges, plateaus, crevices and chasms, and lots of bush land from Kings Canyon to Alice Springs. Our subie bumped along the dirt road and we splashed through the occasional wash outs without problem. Then it appeared – the grand daddy of mud holes. Instead of slowing down this time we accelerated through the middle of the bog. A wave of red mud covered the subie and we rapidly began losing traction. “Come on Sunshine, you can make it!” we pleaded as the tires spun, and then somehow gripped enough to crawl out of the mud. Along this route there were numerous stopping points – swimming holes, a meteor crater, scenic vistas, and places of Aboriginal significance. The ochre pits, a place where Aboriginals visited to collect colored soil, were decorated with shades of brown, yellow, red, and white. By adding water to the soil it could be used as paint for rock walls, caves, tree bark, and for ceremonial body decoration. At the end of the Mereenie Loop we encountered the Finke River, which had swollen into a 100-yard wide shallow river that separated us from the bitumen on the other side. The choice was simple – either to cross this water or back track three days to another route. We slowly crept across the river and emerged on the other side, cheering as we conquered our last river crossing. Once again on tar roads, we closed in on the “big city”. A hot shower, clean clothes, and nice dinner awaited.

Alice Springs is an “outback cosmopolitan” city that offered great restaurants, nightlife, and even a winery. After a dinner of kangaroo, emu, crocodile, and camel we strolled by a pub with a live band and went in for a look. Scotty’s was a locals pub and the eclectic band of guitars, drums, a digeredoo, flute, and numerous other instruments was a favorite entertainment option with the residents. The band got the crowd involved and we were soon volunteered to play in the band. A digeredoo contest for the best male & female player was offered with the prize being the band’s CD, and although Dale deserved the prize I won by default as the only female player.

After the peace & beauty of the outback, trying to sleep the city grated on our nerves. We laid in our tent at a campground in Alice Springs, but the blasting television from a nearby trailer kept us awake. By 3 a.m. we couldn’t take it any longer; marched over to the trailer we yelled out to the owner to turn down his T.V. Evidently he was passed out since we heard no response. We deliberated another option, then snuck around to the back & pulled the plug connecting his trailer to power. The sudden silence startled us -we quickly crept back to the tent hoping nobody had seen this escapade. That morning when we left the cord was still dangling where we had left it.

Driving through the outback surpassed our expectations, best summed up by Henry Miller’s famous travel quote “One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of seeing things.”