(versions of this story ran in Oregonian and World Hum in 2012)

I’ve been working as a professional photojournalist for over a decade yet I still face the same challenge wherever I travel. How can I create meaningful ‘sense of place’ photographs that convey the uniqueness of each location; the sure-footed agility of Himalalyan Sherpas who effortlessly passed me on the trail to Everest Base Camp, the surreal experience of swimming with jellyfish and drift diving with sharks in Palau, or the incredible sense of freedom floating down fresh untracked powder helicopter snowboarding in the Canadian Bugaboos? It’s a never-ending quest to create photographs that create the same emotional impact in the viewer as I experienced during these assignments.

It takes time to allow a place to impress itself on you and to reflect on its significance afterwards. And time and attention are the two resources we lack most in today’s fast paced ADD culture. I was reminded of this challenge once again on a recent trip to Australia’s Northern Territory. I traveled extensively throughout Australia in 2001, but monsoon rains stopped me visiting the top end of the Northern Territory. I hadn’t realized the importance of that trip at the time. The openness of the land, devoid of modern distractions and illusions, allowed me to clear my mind and remove the creative blocks to begin my career as a photojournalist.

I now had my chance to return to the areas of Australia’s Northern Territory I’d missed, traveling with a group of journalists while testing the newest Canon camera. To complete my assignment I’d be required to shoot almost exclusively with this ‘prosumer’ model (the EOS D650 also known as the Rebel T4i in the United States) aimed at the market between consumer and professional; a camera that wasn’t yet released to the market so I wouldn’t have a user manual or an opportunity to test the gear beforehand. And this time instead of three months, I’d have just five days to explore.

Be Fearless, seek engagement

The Northern Territory is nearly 1/6th of Australia’s land mass yet it’s population is just 233,000 – a melting pot of colorful characters including cattle wranglers, miners, immigrants, and Aboriginal people. The Bark Hut Inn is an iconic pub en route to Kakadu. It’s remote; the nearest village is 44 miles away – population 730. The walls are covered with crocodile skulls, water buffalo horns, old saddles, and ranching equipment. It’s the type of rough & tumble place photographers could spend days shooting portraits of the motely cast of characters. I longed to stay to experience the real atmosphere of the place, but unfortunately our fast-paced travel schedule meant we arrived at 9am and only had 20 minutes to explore.

This first photograph I took of the bartender, Kevin Carter, is nothing more than a snapshot. Its essential to get eyes in focus in portraits but there wasn’t enough light in this dimly lit inn for the camera to quickly auto focus. The fluorescent lighting was horrible, but the tiny on-camera flash was not a good alternative either. In despair I began joking with Kevin that I didn’t know how to use my camera, which fortunately put him at ease. We talked about the stories behind his tattoos; his thick Aussie accent was hard to understand but it was easy to see nearly every part of his body was covered in ink. While he was initially reluctant to pose for our group of twenty-six, after our conversation I was able to coax him away from the bar to open shade next to a door at the back of the pub. The second portrait is a dramatic improvement not only for the lighting, but also for the direct and confident gaze that comes from a more engaged encounter.

These portraits were still lacking a ‘sense of place’; but when Kevin turned to walk back into the bar I saw what I was looking for. Environmental portraits don’t always need to show the subject’s face; sometimes the body language provides enough context to reveal character.

Some may call this a lucky shot, but I had been waiting for this kind of natural moment. This composition captures the juxtaposition between the threatening appearance of Kevin’s formidable size and the slight figure of an out of focus tourist in the doorway. The meaning is left to the viewer’s imagination; the ambiguity of this interaction adds a layer of intrigue. For those who work a scene and recognize potential in pre-visualized options, serendipity often falls into place. Without my assignment, I doubt I would have had the nerve to approach and engage Kevin in conversation so quickly; sometimes the window of opportunity is brief; I’m glad that I was forced out of my comfort zone.

Capturing mood

Early mornings are magical in Kakadu National Park, a world heritage site. The billabongs are enveloped in mystery, fog softens the land, and the subdued hues of pastel pre-dawn light reflect across the glassy water. Initially all appears calm, but the park is home to a quarter of the freshwater fish and one third of the bird species in Australia – which were slowly waking up. The illusion of tranquility was broken as dozens of prehistoric reptiles that lurked underwater silently surfaced.

Saltwater crocodile, Yellow Water billabong, Kakadu National Park and World Heritage site, Northern Territory, Australia

The Kakadu visitor guide states “Aboriginal traditional owners welcome you and hope you take the time to look, listen, and feel the country, to experience the true essence of this land . . .If you respect the land, then you will feel the land”. We were transported to an ancient time as we watched the world’s largest and oldest living reptiles approach, the full length of their bodies only visible when ripples revealed their slowly swishing tails. Close up photos of the crocodiles are menacing but I prefer the feeling the wide-angle image evokes, contrasting the tourist boat with the primordial scene in mysterious dawn glow.

Saltwater crocodile, Yellow Water billabong, Kakadu National Park and World Heritage site, Northern Territory, Australia

Gesture, Scale & Perspective in landscape

The landscape of the Northern Territory extends from arid red desert in the center to woodlands, wetlands and waterfalls in the tropical top end. Bender, our tour guide, knew the best locations for sunrise and sunset landscapes but couldn’t do much about the haze from nearby fires. Luckily this haze worked for Darwin’s sunset market scene where a constant stream of people waded in the shallow waters of the adjacent beach, perfect silhouettes against the sunset. It can be difficult to look through a viewfinder directly at the sun so I found the interactive, swivel touch screen of the Canon EOS D650 handy to compose and even shoot these scenes. This screen essentially acts like the touch screen of an iphone, allowing you to zoom, lock focus and exposure, and even shoot with a simple touch of the finger. The sunset colors add drama to the scene, but it’s the gesture of the people that make the shots come alive.

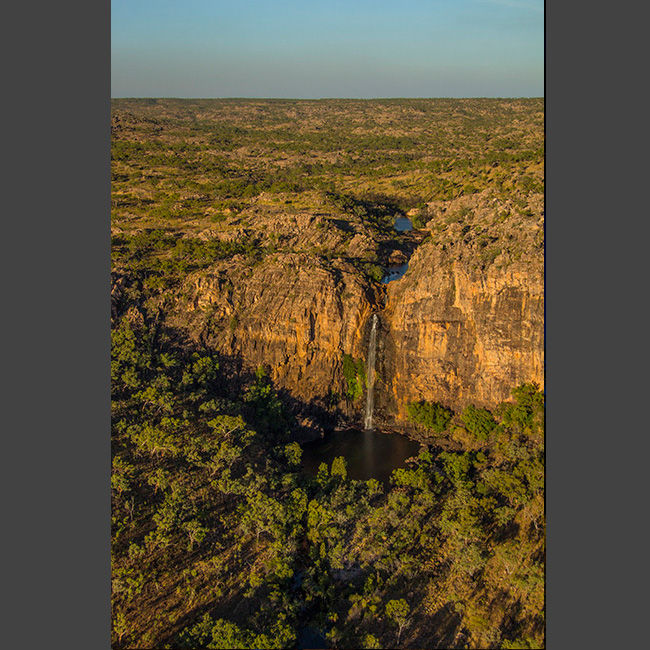

It’s also fortunate that the best swimming holes in Litchfield National Park were ideal for photographing mid day. Landscape photographers will wait for days, weeks, or seasons to find the optimal light to add drama to a scene, a luxury travel photographers can rarely afford. Instead of panicking that I wasn’t capturing the beautifully lit sunrise and sunset landscapes I’d envisioned, I photographed swimmers next to the immense waterfalls to show scale.

This land is home to the Arrernte Aboriginal people who have been chronicling history with their dreamtime stories and rock art for over 40,000 years. They hold title to over 40% of the Northern Territory and believe in a close kinship and spiritual connection with the land. Bruce Chatwins’ book “Songlines”, indicates how difficult it is for an outsider to gain access to authentic stories and I knew it would be impossible for me to capture their essence in photographs.

An Australian I met shared a heartbreaking story of an Aboriginal artist he photographed in the land that inspires his paintings. He learned the artist had not been back to his ancestral land for over 40 years. Amazingly the artist guided him by helicopter back to this area that he had never before seen from the air and was over 1,500 miles away from where he now lived. It was a remote, sparsely populated desert with few discernable landmarks, but the artist used songlines recalled from his family to lead him back to the exact location he was born. As he approached a pile of dead trees and a section of land with no growth, he quietly began to cry. He revealed that this area was the bonfire used to burn his family’s ashes, his entire family of 25 were murdered by the landowner who laced their flour with arsenic and poisoned the water; the artist was the only member to escape this massacre.

His story reminds me of this excerpt from classic essay by Pico Iyer titled “Why we travel” http://www.worldhum.com/features/travel-stories/why-we-travel-20081213/. “Thus travel spins us round in two ways at once: It shows us the sights and values and issues that we might ordinarily ignore; but it also, and more deeply, shows us all the parts of ourselves that might otherwise grow rusty.. . .traveling, we are born again, and able to return at moments to a younger and a more open kind of self. . . .an easy way of surrounding ourselves, as in childhood, with what we cannot understand.” In the context of the outback, I found myself attuned to this story about the Aboriginal artists, resonating with the feeling of universal connection we all have to our homeland.

Power of play

One of the most difficult lessons for me to remember while on a tight deadline is to take time to have fun. In the past, while on an individual editorial or commercial assignment I was rarely able to enjoy the activities I’m capturing; like a voyeur, I’ve worked all angles to best capture others enjoying the scene. Lately I’ve begun letting go of total control in exchange for participating in the experience. I’ve found the easiest way to bring this playful spirit to my work is to find others that share your enthusiasm and make sure they are a part of the adventure. All three people in this scene are professional photographers: Working together we immersed ourselves in the scene and experimented until we captured a moment where all elements came together.

These terraced pools of Gunlom (Waterfall Creek) in the south of Kakadu National Park are ideal for swimming

Australians are famous for their laid back attitudes; although I was initially concerned traveling in a large group, my companions ended up as the perfect subject for many photos.

Ironically, the constraints of this assignment I initially struggled against were the conditions that forced me to return to the roots of my early travel experiences. I was stripped of my typical 50 pounds of photo gear and was forced to lighten my approach both physically and mentally, allowing myself to become a participant in the adventure. I re-learned my early travel lessons: The importance of recharging your creative batteries by trying something new. Flexibility to allow the place to make its imprint on me instead of trying to manipulate a scene to work for a preconceived idea. Most importantly, coming full circle to my early days of travel remembering the experience is more important than the photographs.

The power of just a few expertly crafted sentences can bring me to tears, such as this excerpt from Pico Iyer’s story Why We Travel: “And if travel is like love, it is, in the end, mostly because it’s a heightened state of awareness, in which we are mindful, receptive, undimmed by familiarity and ready to be transformed. That is why the best trips, like the best love affairs, never really end.” I’m inspired to explore by the words of great writers, but when traveling my first instinct is to respond intuitively to visual stimuli. I photograph to freeze these moments, to communicate the nuances I can’t easily put to words, and to respond to emotions I experience but may not immediately comprehend. These images become seared in my mind, and I never feel more alive and in harmony with my surroundings then when I am immersed in a scene working to capture this sense of place in my photographs.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.